|

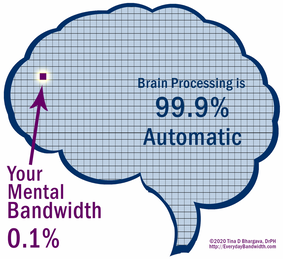

Lately, many elected officials, community leaders, and public health experts, including the US Surgeon General and World Health Organization, have pointed to the phenomenon of “pandemic fatigue” as a key reason for the recent surge in COVID cases. What is “pandemic fatigue”? The World Health Organization describes it as “demotivation to follow recommended protective behaviors, emerging gradually over time and affected by a number of emotions, experiences and perceptions.” Others have more informally described it as people being tired of doing the right thing in terms of COVID risk behaviors. The term “pandemic fatigue” implies that a little rest or extra effort can move us past the phenomenon. But the concept of “pandemic fatigue” does not capture an incredibly important aspect of our experience--bandwidth exhaustion. What so many (if not all) of us are experiencing right now goes far beyond simply being tired of doing certain things. As I’ve described before, the changes in behavior that the COVID pandemic has required are extremely challenging for our brains, and our brains have very clear limits in terms of capacity and ability. The term “pandemic fatigue” does not capture how challenged our brains are right now. What do I mean by that? Well, about 99.9% of what our brains do is automatic—we don’t consciously or actively control it. Only a very small amount—about 100 bits/second, the equivalent of a short sentence—can be under our direct control. This is what “mental bandwidth” refers to. Doesn’t seem like very much, does it? Especially given how many demands there are on our brains in modern times. So, how do we make it work? Well, our brains might have limited capacity, but they are also incredibly capable of learning. When we learn new things, it requires bandwidth. And more complex or unfamiliar something is, the more bandwidth it requires to learn. However, if something—even something very complex—is generally consistent, then our brains use the learning to create neural pathways that allow us to “automatize” certain brain patterns and behaviors. Reading is a good example of this. Learning to read is complex and bandwidth-demanding. But as we continue to read, it becomes an automatic behavior—we no longer think about the process of reading; we do it automatically. We may use bandwidth to understand and interpret what we are reading, but the actual process of reading is automatic. We create these automatic, neural pathways in our brains for many of our day-to-day behaviors. Our habits and routines are ways that we shift things to automatic, so that we can save that precious mental bandwidth for the more novel, complex, or inconsistent brain demands that arise.

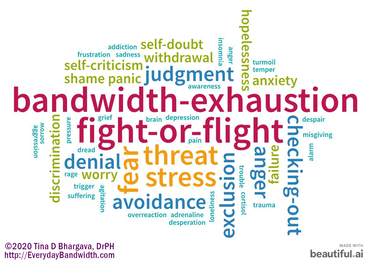

One of the biggest impacts of the pandemic has been the loss of brain routines. So many things that our brains did automatically before, are now bandwidth-demanding—getting our kids to school in the morning, grocery shopping, casual connections with friends and family. And in addition to this loss of routines, it has been extremely difficult for us to create new brain routines. We might get used to doing something, but creating a new neural pathway takes consistency and time—anywhere from 10 weeks to 6 months of consistent “practice” to really etch in those pathways. This means that we are nearly always bandwidth-exhausted—we don’t have enough bandwidth to be successful at all the things we are trying to do. This is beyond “fatigue.” We are in a very challenging situation, with extremely limited brain resources. So, what can we do? For one, it is important to try to limit the things that are draining our bandwidth. This means we want to take care of our physical and mental health as best we can. We can also avoid situations where automatic behaviors are going to put us at risk. This means we may need to avoid gatherings and other places where people are less likely to follow COVID-safe behaviors. Finally, our community leaders and elected officials can play an important role in creating environments that promote COVID-safe behaviors. If our environments and circumstances encourage COVID-safe behaviors, then we need less bandwidth to follow those behaviors. In addition, financial uncertainties are a huge bandwidth drain, so anything that can be done to support the financial well-being of individuals right now, will free up considerable bandwidth. Bandwidth exhaustion is widespread right now. It makes informed decision-making extremely challenging. To make a meaningful impact in people’s behaviors right now, we must clearly recognize the role of bandwidth limits and bandwidth exhaustion, and take steps—individually and as communities—that will promote safer behaviors, and reduce the spread of COVID-19.

0 Comments

While we may not like being in the midst of a pandemic, mass protests, economic recession, and murder hornets, that’s where we are. But however hard all of it is on us, it’s even harder on our brains. Why? Because the massive changes and uncertainty that we’ve been immersed in have huge impacts on our “mental bandwidth.” If you haven’t heard of mental bandwidth, it’s kind of like your thinking resources. In general, most of the work our brains do is automatic—not within our awareness. Only about 0.1% of our brains’ resources are within our conscious control—equal to about one short sentence each second. That’s it. That tiny bit is our mental bandwidth. It is extremely limited and extremely important. We need it to learn, to make choices, and to do almost anything of meaning in our lives. Our mental bandwidth is especially pertinent right now, because the extreme drains on it right now have created a unique “brain environment” that primes us for protest and activism. Point #1 - The current state of the world exhausts our bandwidth. The pandemic has brought with it immense uncertainty, which our brains see as a threat, thus requiring massive amounts of bandwidth. As humans, we yearn for certainty. If you need proof of that, just ask any parent of a school-aged child what they’d give for certainty about school opening “normally” this fall. They know as well as anyone, uncertainty devours our mental bandwidth. Also, since the start of the pandemic, many of our routines have been changed or lost. This is really hard on our brains. When something is routine to us, our brains do it automatically. But when something is unusual, we have to use our bandwidth. Given the sheer number of routine things that are no longer routine for many of us, our brains are bandwidth-exhausted. For some of us, our brains are also jarred by finally recognizing (or admitting to) the undeniable and insidious presence of racial injustices in nearly all of the spaces, practices, and beliefs that have been long been upheld as “normal” and acceptable in the United States. This disrupts typical brain narratives—that everything is pretty good; we are a fair and just society; and if we try hard enough, we can do anything. This mental disturbance is also extremely bandwidth-demanding. Point #2: Our brains our primed to disrupt unjust norms. All of this is clearly a lot for our brains to handle. But while the brain struggle is undeniably disturbing, it also presents an exceptional opportunity to “rewire” some of our most elemental ways of being in the world, and to fundamentally change societal systems and structures that guide our actions. To build justice in an unjust society, we need to be willing to disrupt “normal,” which can make our brains very uncomfortable. Usually, our brains respond to this discomfort by retreating to safety and falling back on the actions and narratives that are automatic, and less bandwidth-demanding. That’s why, normally, we tolerate clear injustices, and don’t revolt when, for example, low-income communities continue to go without grocery stores or affordable medical clinics, simply because it’s in the best interest of corporate profit. Since the pandemic began, many of our brains’ “safe spaces” are in chaos, and we spend much of our time in brain discomfort, no matter what we do. Because we don’t have so many automatic routines to fall back on, ANY actions we take are going to require bandwidth. So because our new choice is between having brain discomfort and allowing injustices to continue, or having brain discomfort and trying to stop those injustices, taking action actually feels less brain-demanding than usual, so is more likely to happen. The outrage about the killing of George Floyd demonstrates this. Why did we see such activism this time? Because our brains were submerged in the excruciating uncertainty of a pandemic. When George Floyd was murdered, it undermined our inherent belief in justice and triggered our need to act. But because we couldn’t retreat to the brain safety of routines, we stepped up in opposition to the injustice. Disrupting in the midst of disruption was more doable, because our brains were (and still are) primed for things to be different. We must take advantage of this the continued disruption from the pandemic. Point #3: Now is the time to act. Some may say, “Wait, didn’t you just say my brain is exhausted from everything? How can I afford to do things that are challenging; that I haven’t done before?” The response is simple—you can’t afford not to. Now might be one of the rare times in our lives when we can invest the time and energy and bandwidth into the fight for justice and expect to see lasting change. We must not let this opportunity pass. For some, whose mental bandwidth was exhausted long before the pandemic—by extreme financial worries, lifetimes of discrimination, and nearly constant threat and uncertainty—this is harder to ask than ever. It’s like asking someone who spent days fighting a fire to build themself a new house before they rest. We must recognize and respect that some people make life or death decisions when they choose how to fight this fight. But, for the rest of us, this is the time to step away from norms that perpetuate injustice and into the revolt. We could try to settle back into old norms to reach that comfortable brain state, but it’s not going to work. The pandemic shows no sign of letting up. The uncertainty and disruption will be with us, no matter what, for a while.

Choosing not to go back to old norms will make our brains uncomfortable; it’s true. And probably those who hold power, and thus zealously support those norms, will try their best to make our lives uncomfortable too. But we have to move through this distressing time somehow; our brains are giving us a chance to do it with purpose. To move forward, we must focus on action, not on thought. Alicia Garza, co-founder of Black Lives Matter, tweeted on May 27th, “I don’t have easy answers for you. And honestly I want us to stop looking for them and start supporting the organizing work people are doing and have been doing.” This is the heart of the answer. There are wise and strong and exhausted people out there doing this work, and we must help. The Black Lives Matter website has excellent starting points. Local action can be identified through a number of online sources. And we can look at our own homes, schools, workplaces, or communities, and begin to dismantle racism and implement anti-racist practices there. This will not be an easy task, and we (and our brains) may be quite uncomfortable with it. But we’re not going to find comfort in a pandemic anyway, right? We must not let this opportunity slip by. Action is necessary, and our brains are primed for it. I was talking to my older brother on the phone the other night. We were catching up on the last couple of months of “pandemic life” and something simple he said really struck a chord with me. “I’m over it,” he said. Yes! Me too... I feel exhausted from all the things that have taken place since February, and especially since the stay-at-home orders in March. And I could hear the same tone in his voice that I try to keep out of mine. That “I’m-going-to-wear-a-mask-but-I really-don’t-want-to” tone. Of course, he’s a computer engineer. So if he chooses to leave his house without a mask, it wouldn’t necessarily be seen as a flaw in his character. I am a public health professor. If I ran into anyone I knew in public without a mask on, it would undermine my entire professional AND personal integrity. And it should! Despite the current controversy, there are very few scientifically legitimate reasons to not wear a mask, especially given the rising cases of COVID-19 that we are seeing in the US since we began re-opening. And, for me, there are very few legitimate reasons even to leave the house. With a history of cancer and other medical “stuff,” it would be tough to argue that I’m low-risk. And my mom, who I live with, is definitely not. The once-a-week curbside grocery pickup and the occasional medical appointment are about all I can justify if I want to keep us safe and healthy. But, I still don’t want to wear a mask. Or socially distance. Don’t get me wrong, I’m going to anyway. I just don’t want to. It could be that I’m just a very bad and uncaring person, and that’s why I don’t want to do these things. Certainly the numerous memes and persuasive pleas to view masks as acts of kindness or respect would support that view, but I’m hoping that’s not all there is to it. That point of view, while both true and valuable, fails to account for the unconscious, not-within-our-direct-control, powerful messages our brains send us to NOT wear a mask. As I discussed in my last post, during this pandemic we have lost many of our daily routines, which drives mental bandwidth demands up, and we have also been immersed in uncertainty, which significantly wastes the bandwidth we have. Given this, I believe my low-bandwidth, highly-reactive “pandemic brain” is the real reason for my reluctance to wear a mask and my annoyance with social distancing. We are a few months into a pandemic, and our brains want a break. To get a break, the easiest things to do would be either to go back to our old routines, or to create some certainty. The problem with going back to our old routines is, of course, that many of them are still not possible or useful. And for some of us, they won’t be useful for the foreseeable future. A close friend, who used to commute to work for a fairly standard 40-hour work week, was recently told that she would be working from home “indefinitely.” The commute routine? It’s gone. Those routines that we could feasibly return to, simply may not be safe during this pandemic. For example, my friend who spent last summer practically living in her mom’s swimming pool with her parents and her young children, is mostly making do with a 10-foot inflatable pool on the deck. Not bad, but not what they were all yearning for… However, with her mom undergoing cancer treatment, it’s the safest option for them right now. Creating certainty right now is also not really an option for a “brain break.” We are trying. In fact, we are REALLY trying. You don’t have to go far to hear the anxious pleas of parents wanting to know when (or if) their children will go back to school, or to come across someone who is desperately planning a vacation, “just in case.” Hey, I think my brain would be happy if the grocery store hours would just stay consistent! But, in terms of certainty, I don’t think we’ve yet seen the light at the end of the tunnel. So our brains are uncomfortable and bandwidth-exhausted, and longing for a break. You know what doesn’t feel like a break to our brains? Wearing masks and social-distancing! In fact, they are quite the opposite of a break—they create more work for our brains because they require building new routines. Staying at least 6 feet away from someone is not what most of us are used to. If you’ve tried to have a “socially-distanced visit” with friends, my guess is that you slowly drifted closer and closer together, as if you couldn’t help it. And wearing a mask—for most Americans, at least—is not a habit. Given that building new habits can take 3-6 months AND use up a lot of bandwidth, these new “healthy” behaviors are merely an additional source of increased bandwidth demands. No wonder our brains don’t want to do them! Wearing masks and socially distancing can also take away from the things we try to do to refresh our bandwidth. Things that might normally help us relax and enjoy ourselves are suddenly tinged with irritation and discomfort. It’s like spending the day at the amusement park in shoes that hurt your feet. Yes, you have fun—kind of. But you’re also more annoyed and impatient, with a strong desire to ditch those shoes as soon as possible. The problem is, we need our shoes to protect our feet… Likewise, we need masks and social distancing to protect our lives and our loved ones. So what do we do? You’re probably not going to like my answer. We push through, and do it anyway. Because the pandemic is not going away soon, and wearing masks and social distancing are what’s going to help to keep all of us as healthy as possible. Here’s the good news—if we keep consistently doing these things, they will become easier for our brains to do. The trick is to be consistent, so the brain gets used to doing them, and they become less bandwidth-demanding. Every time you leave the house, the mask goes on. Around someone not in your household? Put up your imaginary 6-foot force field. How do we move past those strong brain messages to forget it all and just do what we want? It’s not easy. Our brains can be really loud and persistent. And we can’t control our brain messages, or how much bandwidth it takes to do any particular thing. We can control our actions. That means that we can hear our brain messages, recognize what they are offering, and still choose to do the behavior that serves us best. Understanding that reluctant brain messages are natural, and do not make us "bad people," can help. Judging ourselves as “bad” for not wanting to wear a mask or socially-distance is not helpful—it uses up more bandwidth and can make it harder to commit to doing what we know is actually the healthiest choice. Making others feel bad about their reluctance to take these actions also doesn’t help. When other people feel judged, it uses up their bandwidth, and that doesn’t help them make wise choices either. Again, don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying that we just do whatever our brains want. We all still need to be wearing masks and social-distancing. At the same time, we can be compassionate to our poor, exhausted brains by recognizing that taking these actions taxes our bandwidth! We can give ourselves, and others, credit for doing things that are not as easy as they seem.

Wear your mask, and keep your distance. Your brain may not like it at first, but it matters, and you can be proud of doing it. The world may never know… but "mental bandwidth" is the key to beginning to understand. “I think everyone has lost their minds,” my friend expressed to me over the phone a few weeks ago. “The pandemic drove them all crazy, or maybe they’ve just always been stupid.” The details of her story aren’t the point of this story, but I’ll just say it involved a grocery store, masks, arrows on the floor, and, of course, the crazy people. I interrupted. “They’re not crazy, it’s bandwidth.” “What?” “It’s bandwidth,” I insisted. “Yeah, but everything is bandwidth with you.” I swear I could hear her eyes roll over the phone. I get it. Yes, everything is bandwidth to me. But, hey, that’s because everything IS bandwidth! I’ve been studying it for over 10 years, and what I’ve learned above all else is that using a mental bandwidth perspective can completely transform what we do and how we do it—for ourselves and for others. People just don’t know it—yet. 1. Bandwidth is extremely limited and extremely important.What is “mental bandwidth”? Well, it’s the incredibly tiny amount of brain resources that we have conscious control over. Our brains process a ton of information, but only about 0.1% is within our control, meaning that our brains do about 99.9% of things automatically. If that sounds high, try to remember the last time that you thought about inflating and deflating your lungs to breathe, or bending your knees to walk. Have you ever headed somewhere and ended up somewhere else, because that’s where “your car” decided to go? That’s your automatic processing kicking in. Our bandwidth—the part we have conscious control over—is tiny, about equal to a short sentence each second. It’s extremely limited and extremely important. We need it to remember things, to learn, to be creative, to be patient, and also to ignore our more primitive instincts and do things like be polite. Like my friend was being when I interrupted her to bring up bandwidth. Again. She sighed, “OK, why is it bandwidth this time?” I could tell she was kind of annoyed, and I could have told her being annoyed would waste her bandwidth, but I didn’t think she wanted to hear it at that moment. 2. Many things steal our bandwidth that are largely out of our control.Annoyance can eat up bandwidth? Yep. Our bandwidth is supposedly the part of our brain we have “control” over, but actually it’s more like the part we could have control over. In reality, a whole bunch of things steal our bandwidth that are largely out of our control—worry, fear, illness, self-criticism, being excluded, and a million other things. All humans have about the same amount of bandwidth to start with, but depending on our circumstances, we can have very different amounts available to actually use. And right now we are in the middle of a global health crisis that not only threatens our lives, but also turns them upside down. Threats are tough enough on the brain. They switch on the fight-or-flight response, which actually causes our brains to shut down some of our bandwidth. But the threat stuff is just a start. 3. The loss of routines during the pandemic has led to huge, unexpected bandwidth demands.The pandemic has led to shut-downs and stay-at-home orders that took away a LOT of our routines. I don’t know about you, but “getting ready for work” is a much different experience for me now than it was in February. And during those first few weeks of stay-at-home? Honestly, all I had to do was work from home instead of work from my office. I usually do half my work from a Panera anyway, why would working from home be such a big deal? Yet I was exhausted and irritable and anxious for weeks. Why? Well, because bandwidth (I told you, everything is bandwidth). Here’s the thing—our routines and habits allow us to shift things OUT of our teeny, tiny bandwidth, and to use our huge amount of automatic processing instead. We don’t really *think* about the things we do routinely. That’s why we automatically get our kids ready for school on a Monday before we remember that it’s a teacher service day, or why we “don’t remember” what we ate for dinner last night. The problem is, when we take things off auto-pilot, our brains have to work hard. We need bandwidth for anything that is unusual, even if it’s simple. So when lockdowns went into place, all of a sudden we shifted a ton of daily activities from our automatic brain processing, to our bandwidth, meaning there was not enough bandwidth to go around. I call that “bandwidth exhaustion.” 4. Our bandwidth is exhausted from all of the pandemic uncertainty.The second thing the pandemic did was to create uncertainty. A LOT of uncertainty. And our brains really, really hate uncertainty. When our brains can’t get a grasp on what’s going to happen next, they start trying to fit pieces into places that aren’t there—and wasting extraordinary amounts of bandwidth. Have you ever been waiting to hear about something really important, and when you hear—even if it’s bad news—you feel relieved because at least now you know? When we “know,” we free up bandwidth. When we don’t know? More bandwidth exhaustion. There is an enormous amount of “not knowing” during this pandemic. As many experts (and memes) have informed us, we don’t make the timeline, the virus makes the timeline. We don’t know when things are going to get back to “normal,” or even if they ever will. That drives our brains crazy and we waste a big portion of our extremely limited bandwidth trying to force things to be certain. “That’s why you’re being so judgmental and controlling,” I explained to my friend on the phone. “Excuse me???” Oops. OK, maybe that wasn’t the right way to say that. “I mean, that’s why people are being so judgmental and controlling.” Right. That helped, I’m sure. 5. Bandwidth exhaustion can trigger a threat response that can make us act more controlling, angry, or avoidant.It’s true. Bandwidth exhaustion can trigger us to be judgmental and controlling. Or alternatively to turn to avoidance or denial. This is because when we have ongoing bandwidth exhaustion, we also have ongoing “failures” as we try to do things that need bandwidth, but don’t have enough to do them (Um… Anyone else ruin their healthy meal planning during the pandemic? No? I don’t believe you…). All of those little failures add up in our brains and feel like threat. It doesn’t matter if a situation is actually threatening. If the brain feels like it’s threatening, then that fight or flight reaction kicks in. But in the vast majority of day-to-day situations for modern humans, the threats that we experience don’t require us to actually fight or run away. Instead of physical “flight,” we mentally run away by avoiding the things that seem threatening or by checking out from reality altogether. Have you noticed anyone during the pandemic who is binging more than usual? Food, alcohol, video games, reality TV—they’re all ways of checking out from the things that are taxing our bandwidth. And if we don’t “allow” there to be a pandemic, then we don’t have to do anything differently, and we can get back to those comfortable, low-bandwidth routines. We have mental ways we “fight” too. Some of us get angry and aggressive and lash out verbally at those getting in our way or trying to control us. Which is ironic, because another “fight” mechanism is to try to control everything. If we can build an illusion of control, we can feel like we have certainty for a while. Because if our kids do all their homework a week ahead of time, or our partners put the dishes in the dishwasher that way that they’re supposed to, or the grocery clerk puts the bread at the top of the bag, instead of squished in with the canned goods, then everything will be alright. That is, until the reality hits again and reminds us that there is no real control in a pandemic. 6. Bandwidth exhaustion can push us towards right-or-wrong thinking, which makes us more likely to be judgmental.Bandwidth exhaustion also leads to judgment—of others and of ourselves. Bandwidth-deprived brains want everything to be yes or no, right or wrong, because then it feels much easier to make a decision. Out of desperation, we begin to decide what’s “right” and “wrong” so we can make it through the daily bandwidth demands. Wearing a mask? Right. Having other people over to our house? Wrong. The thing is, the world isn’t that simple, especially during a pandemic. There’s a ton of gray area. But it drains our already-depleted bandwidth to try to sort it out. So when you decide for yourself, mask = right, and then see someone without a mask, your brain is going to scream “wrong, wrong, wrong!” Our bandwidth-exhausted brains are very (over)reactive, and thus very judgmental—even if that’s not the kind of person we would prefer to be. “So if it’s bandwidth, there’s nothing I can do about it, right?” my friend asked.

Now it was my turn to roll my eyes. Of course we can do something. What can we do, and what can others do? Well, that’s a whole other story, and I don’t want to ruin the ending. Interested? Let’s talk. Or check out more resources here at http://everydaybandwidth.com. My journey to bandwidth research included an overwhelming graduate program, a bunch of people in a research study who were struggling to live healthier, and a mentor who encouraged me even though I was thinking pretty far outside of the box. Last year I was presenting about bandwidth at a community college in Pennsylvania, and one of the audience members—a physics professor—said, “Wait, what do you mean by bandwidth? Because I think of bandwidth in terms of the frequency of a signal. I don’t see how this relates to that.” This question was not surprising, although it did make me wonder if I needed to brush up on my presentation planning… But it certainly wasn’t uncommon for someone to be confused by my use of the word bandwidth to refer to human brain resources rather than unfamiliar physics concepts or internet service. When I talk about “mental bandwidth,” I’m referring to the extremely limited amount of conscious cognitive brain processing resources available to accomplish tasks at hand. I can’t take credit for calling this concept “bandwidth.” In 2013, Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir published the book Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much, and they used the term “mental bandwidth” as follows:

In 2016, my research collaborator, Dr. Cia Verschelden, was reading Scarcity, and it was she who brought the term into our conversations. She tried it out when she shared her work and found that it really resonated with others, so we started using it jointly in our scholarship of teaching and learning work. I had been studying bandwidth for a while by then, since 2009 when I started my research for my doctoral dissertation. At that point I called it “attentional resources” or “conscious processing resources,” as those were the terms most used in the neuropsychology literature I was studying. And at that point, as a Public Health student, I was trying to better understand how limitations in bandwidth might affect people’s abilities to change their health behaviors, like healthy eating and physical activity.

After a few years of serving as a research project coordinator at the University of Pittsburgh, I had begun to look into bandwidth limitations as a possible explanation for why some of the participants in our lifestyle change research studies were less successful than others. The program we were researching was designed to the reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes, and involved an online program with lessons, health coaching, and tracking of food, physical activity, and weight. I was often responsible for calling the “difficult” participants who had stopped logging in to the program or coming to their research visits. When I finally reached them on the phone, they would often explain the challenges that they were facing with lifestyle change—care-giving for an elderly parent, working in jobs with excessive and unpredictable hours, making meals for others in the household who weren’t trying to eat healthy, or managing complicated chronic health conditions. What I noted was that they seemed as motivated and willing to work hard as the participants who were being successful with and consistently using the program. The problem seemed to be that they were mentally exhausted from the parts of their lives that were unpredictable and out of their direct control.

At the time I was working 50+ hours a week in my research job, being an almost full-time student in a doctoral program, and dealing with my own complicated health issues. I could understand what might be making things so challenging for them, because it seemed like the same thing that was making things so challenging for me. I felt like I didn’t have the mental capacity to keep track of all the different pieces of all the different parts of my life. I could do two things well at a time—my job and my degree, or my health and my job. But I couldn’t seem to find a way to do all three at once. And I felt like my brain kept holding me back. Even when I had time to work, I couldn’t pull together the focus or clarity of thought to make progress on the tasks at hand. So I started to wonder—what amount of “brain resources” were required for the things that I was trying to do, or trying to get our participants to do.

I found an article by researcher Deborah Cohen--"Eating as an Automatic Behavior”—that tied my interest in brain demands to my passion for public health. My subsequent dive into psychology, neuropsychology, cognitive science, and health behavior research fascinated me. I connected with faculty at the university who were outside of School of Public Health and interrogated them about how to design cognitive response-time tests that I could use with the participants in our research study.

In 2012, I completed my doctorate with a dissertation that focused on how mental bandwidth affected the success and participation of different individuals in a weight loss program. I can admit that my results fell short of being ground-breaking, but it was only the start of my interest in the topic. Now, I have extended my bandwidth work into domains beyond health behavior—public health, higher education, social equity, workplace productivity, etc—and have used my understanding of bandwidth to design and recommend strategies for improving success in these domains, as well as to understand the impacts of different types of public policy. Through this website and blog, I hope to connect more people to this concept, to provide opportunities for others to benefit from the bandwidth perspective, and to learn more about other perspectives that can expand the impact of this work. I look forward to working with you! - Dr. Tina D Bhargava |

AuthorDr. Tina D Bhargava is a professor at Kent State University, and a bandwidth scholar, teacher and liberator. She is the founder of everydaybandwidth.com. Archives

November 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed